Sowing Seeds & Bearing Fruit by Donna Koh

If you are currently surrounded by towers of WA3 (Weighted Assessment 3) or preliminary exam scripts and administrative work, counting down to the end-of-year examination and semester break, and already besieged by plans which are underway for 2026, congratulations – you are definitely in the thick of Term 3, which is more likely to feel like Term 30 at this point. Something about school life makes our thinking and behaviour operational and survival-centred more than we would like to admit; what is inspirational and drives motivation to flourish takes a backseat. Yet education ought not to be about survival. On another note, the dogged determination to check off a long list of goals and targets calls us to question if education ought to be only about achievement and success. So, what are we neglecting in the routine but dangerous pursuit of completing the term and school year with as many notches in the belt as possible, but at our young people’s expense, and at the expense of the true purpose of education?

What benefits do young people reap from school activities and experiences that are carried out in survival mode and/or for success? I have lost count of the number of times my students have looked at me wearily – clutching the latest assignment from the Ten Year Series which is filled with more crosses than ticks – but still earnestly persevering to “improve”. I am equal parts proud of them for their resilience yet cannot help but feel so sorry for them and how tired and burdened they must feel, juggling the weight and expectations of society and stakeholders, including of their own. Is this what it means to honour the dignity of a child? If the purpose of education is to develop the young person in their best interest, in what way is it helpful or effective when we do more? The month of September begins with Teachers’ Day celebrations and as we enjoy the tokens of appreciation and affirmation from the young people we spend so much time with, it seems as good a time as any to consider: what does care for our young people and their best interest really look like; how can we show care with intention; and on a fundamental level, what are these best interests?

With the belief that excelling is important, society has conditioned us to reach for these common definitions and indicators of success: academic excellence, career progression, material acquisitions… But the pursuit of success in today’s landscape is a disquieting consequence of our fixation on meritocracy, which Michael Sandel (in his book The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good) argues has steered us further away from what actually contributes to the common good. What he calls the “rhetoric of rising” – an emphasis on individual effort and achievement, and a sense of deserving-ness which ultimately leads to hubris and a disregard for systemic inequalities – also creates a great deal of stress and entitlement, while dangerously influencing our young people to believe that success must look a certain way. What is even more troubling is how meritocracy has undermined the dignity of the human person and work. Education can indeed help our young people succeed and excel, but at what cost?

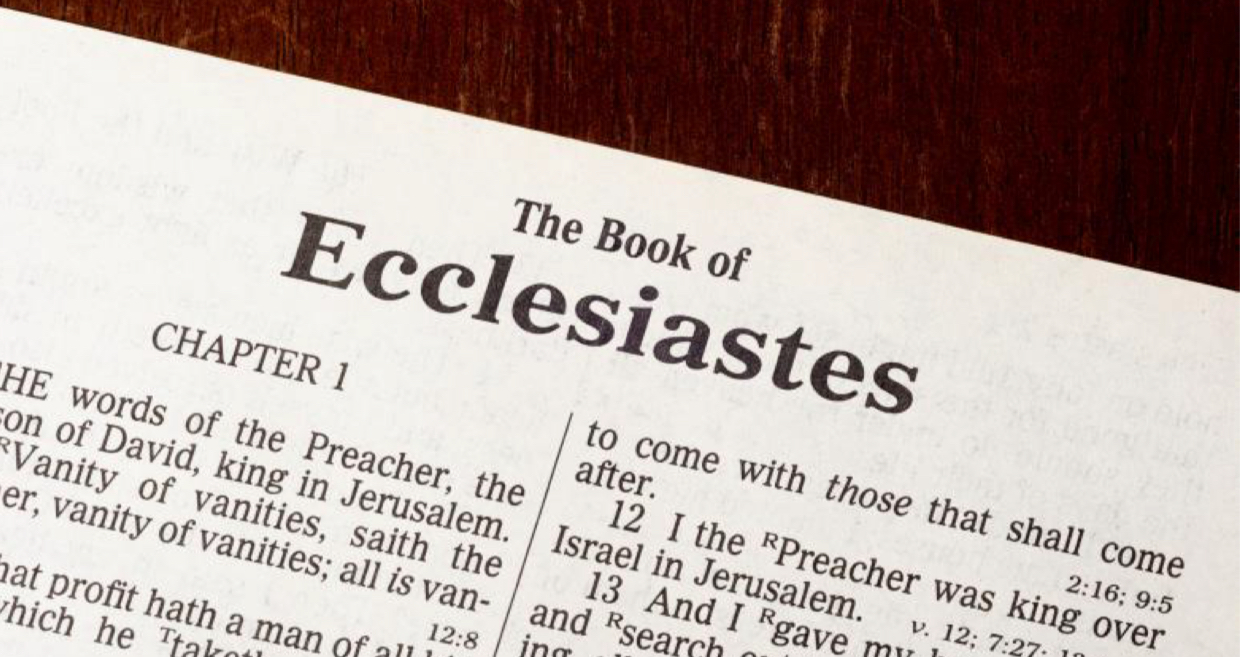

Think about what we find disturbing about the state of the world today: exploitative behaviours on those who are already disadvantaged and marginalised; socioeconomic and mental health issues that evolve in disturbingly unimaginable ways; chasing technology that progressively destroys the planet and erodes our humanity… the list goes on. Catholic education aims to teach young people to respect the dignity of the human person and to care for the common good. Yet at its heart, Catholic education also practices what it preaches, in the way that it respects the dignity of the human person and cares for the common good. At Sunday Mass recently, the first reading from Ecclesiastes 1 seemed to me a fitting verse for the September Sowers theme:

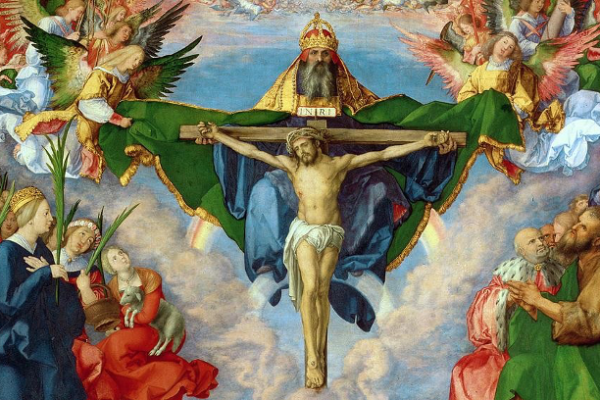

“Vanity of vanities, says the Preacher, vanity of vanities! All is vanity. What does man gain by all the toil at which he toils under the sun? A generation goes, and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever…”

Our achievements, possessions, and accumulations are fleeting and of the world; none are as precious and fulfilling if they are not centred on God. Do our actions and attitudes harm the planet and our fellow human beings, or do they protect our common home – and our only home — and give life to others? What values does the Catholic faith teach that enables us not just to succeed as an individual, but to flourish together with others? As Catholic educators, how do we role-model what we want our students to demonstrate? If we chase excellent academic results, won’t they do the same? If we persist in using AI for work under the guise of saving time, dare we hope that our students become skilled and discerning communicators themselves?

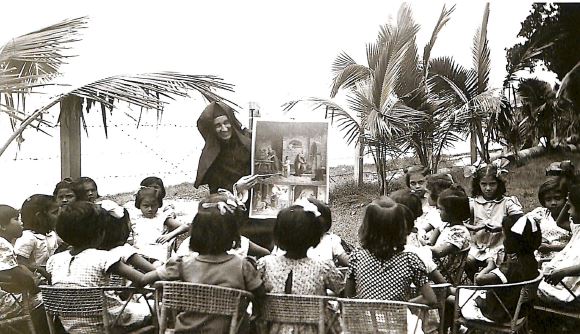

Were we to have the prescience to know every single implication of today’s actions on the future, what would we learn, relearn, unlearn, do and undo? One way to help young people care more for the common good is through an interdisciplinary curriculum, where the Arts and Humanities are integrated into Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (hence, STEAM). The holistic perspective and understanding developed in an interdisciplinary curriculum would foster empathy, social awareness, as well as a deeper humility and responsibility for our planet and its inhabitants. In turn, this sense of belonging and community strengthens their care for the common good and purpose, redefining what it means to safeguard and work towards people’s “best interests”. And how else can our young people be living testimonies of Catholic education if not through the gifts and fruits they bear – peace and joy under any circumstance instead of anxiety and a desire for more; goodness, with the courage to choose to do the right and good thing; love of God and neighbour, honouring God’s creation through their values and actions; amongst others. Teaching our young people to fix their eyes on God – and honour Him – is perhaps the single most powerful thing we can do for them as Catholic educators.

It is indeed complex to hold so much tension in education. Educating young people can sometimes be an exercise in conflict management, both external – across stakeholders’ desired outcomes – and internal, when we grapple between what we must do and what we want to do for the young person. Yet reconciling practice with what we believe in our heart of hearts to be good for our students is also our call to wisdom and to live out God’s enduring truth for teachers: to keep sowing seeds and producing fruit that enriches His creation.

Credits: Image from Canva Pro