The Feast of the Transfiguration By Ann Ang

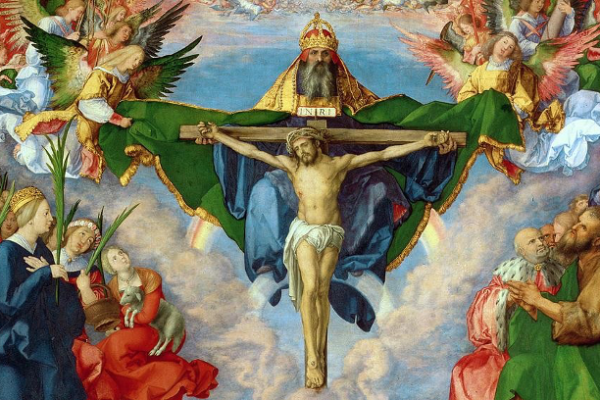

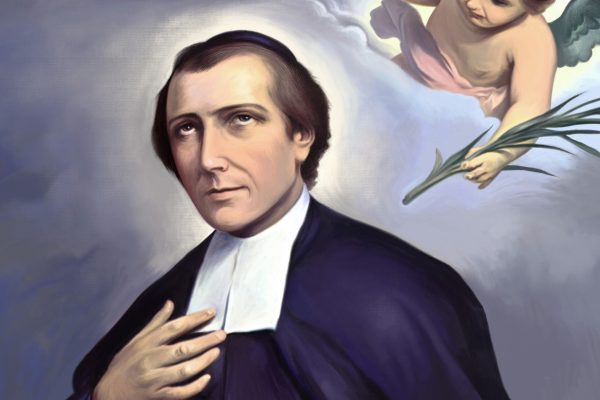

The feast of the Transfiguration (which the Church will celebrate on 6 August) is mentioned in the three synoptic gospels, by Saints Matthew, Mark and Luke. Across all three, the account is similar. Jesus is in the middle of his ministry in Galilee, but he has also begun to foretell the means of his suffering and death to his disciples. At that time, disciples such as Saint Peter did not have the benefit of hindsight, like us, or the great experience of Pentecost. One day He brings Simon Peter, and the brothers James and John up a high mountain. The three disciples saw Jesus conversing with Moses and Elijah, and as they gazed at him, his face is transformed and his clothes shone with dazzling white. In the gospel of Luke, Peter volunteers to make three tents, one each for Jesus, Moses and Elijah, but he is off-the-mark, because a cloud appears and covers them with its shadow. The disciples are terrified and fall on their face, and God speaks: “This is my Son with whom I am well pleased—listen to him!”

Source: Ministry to Children

How do we come to understand the divinity of God, and by extension, the goodness of God’s creation as it emanates through our world, nation and society? Most of the time, like the disciples, we are concerned with the people we know and meet, and with our own cares and concerns. Appreciating our role in relation to the greater good requires a leap of faith, and also a certain sensibility for larger, longer-term aims. God is in the world, but it is certainly difficult to balance focusing on Him, while also doing his work in the world. Like Peter, we often want our own actions (making tents in his case) to speak louder. In fact, Peter was often chastised by his Master. Just before the Transfiguration, he is first recognised by Jesus as the Rock of the church, for declaring Him the Messiah, and then swiftly rebuked in the next chapter, when Peter reacts with shock and horror, instead of humble acceptance, to Jesus’s foretelling of his suffering and death.

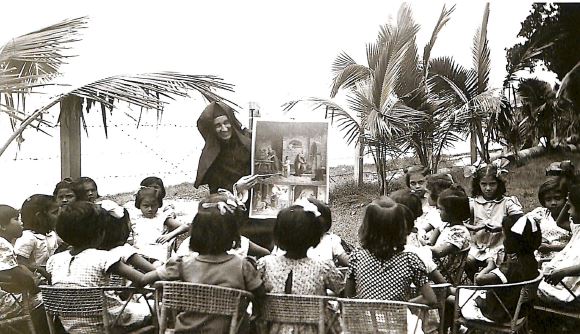

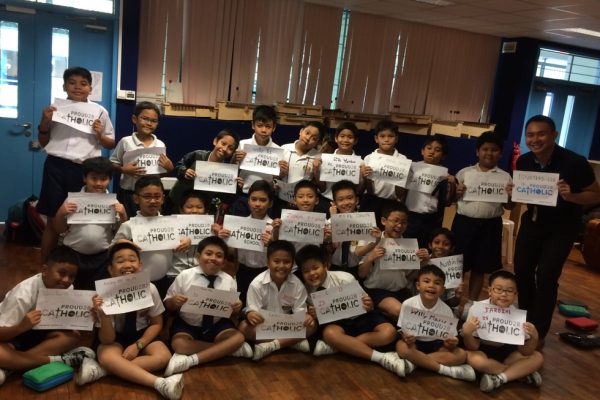

For us educators, it is hard to keep the larger outcomes of education in view. We trot out the same tired truths: loyalty, obedience, responsibility and the common good. But what the Transfiguration shows is that apprehension and understanding of what is divine and larger than us, is not a matter of content or skills. Anyone, even us teachers, can repeat these words, but the Transfiguration teaches us that God’s true nature leads us to a sense of awe, wonder and reverence—in other words, a spiritual response. What the world conventionally calls intelligence implies practical and transparent objectives. What is enduring, however, is not something that can be immediately apprehended. Pedagogically, it means that we could consider letting our students be interested in places, stories, lives and experiences that come from another part of our nation or society that they don’t usually encounter. Personally, I believe that when we connect, in an open-hearted way, with something or someone that is different, that sense of curiosity and interest transforms us; not by making us smarter, or better than others, but by restoring us to a child-like sense of humility and play. We don’t and can’t know everything, but we can trust in what is bigger than us, and work towards its eventual, divine good.